Life at the Bar – A Sad, Sad Case

Over the years, I must have seen hundreds of defendants, but there are very few whose faces I can visualise now. One I can wasn’t even my client. I was sitting in court number 2 at West London Magistrates, waiting for my case to be called on, when a young man probably aged around twenty was guided into court by a police officer. He was quite tall and of a sturdy build; his black hair curled so tightly that his scalp was visible. In profile, his nose was straight without any hint of his African ancestry. His clothes were scruffy; a pale blue shirt hung out of his ripped jeans and his trainers looked as if they were a size too small. Despite it still being early spring he had no jumper and no coat with him.

He was before the court for the offence of ‘being in possession of an offensive weapon.’ A police officer got in the witness box and described to the court finding the young male in the recess of a shop door, sitting on the floor clutching to his body a large stick, which the officer produced. The stick looked like a branch of a small tree, a few inches in diameter and rather twisted.

Had he threatened anyone with the stick, the magistrate asked.

‘No,’ said the policeman.

‘Is it adapted in any way, for example, a nail in one end, or sharpened to make it into a weapon?’

‘No,’ said the officer.

‘Did the defendant say anything to show why he had this stick?’

‘When I arrested and cautioned him,’ the policeman held his notebook up and read from it, ‘It’s my only friend.’

Throughout the proceedings, the young man had been totally passive, his eyes looking inward as there was no future to see. His lawyer got to her feet, but the magistrate said she didn’t need to address the bench as he and his colleagues were going to dismiss the charge but not before the probation officer had spoken to the defendant and arrangements had been made for him to go to a suitable hospital.

I doubt he would be treated so well now as there is such a shortage of places for the mentally ill in our hospitals and that young man needed a place where he felt secure and would be treated appropriately.

Life at the Bar – The Rapist from Iran

Although I have been in close proximity to quite a number of very violent men I have only been assaulted twice in the course of my work. The first time was whilst I was still working as a solicitor and had been instructed to represent an Iranian man who was charged with a number of rapes. He was in his late twenties and, when I first met him, was quite charming. Because of the seriousness of the offences I instructed a QC to defend him.

The allegations divided into two groups. The first two were made by the same young woman, who said she had met the defendant in Covent Garden where he had told her he was a student, newly arrived in London and knew no one. She took pity on him and at the end of the evening she invited him to her flat. It was there that he had forced himself upon her on two occasions, despite her resistance. His case was that she was a willing participant in the sexual activity. My client had left the flat the next morning and despite the police being called immediately they were unable to apprehend him.

The second set of offences was rather similar, but took place a few months later. Again he had met a young woman who was sympathetic to him and invited him back to her flat. What he was unaware off was that she was living with a female partner, who returned to the flat later that night and found the defendant with her lover who was clearly very distressed. The partner called the police and he was arrested running away from the premises.

We made an application to sever the two sets of allegations and to our surprise the Judge granted it. My client was acquitted of the first group of rapes but was convicted of the second. His defence that the woman had consented was not believed by the jury, not least because her sexual preferences were quite clear. He was sentenced to seven years in prison.

Immediately after being sentenced he was held at Wormwood Scrubs and soon I began to receive letters from him telling me he wanted to appeal against his conviction. We had already told him he had no grounds to appeal when we saw him in the cells below the Old Bailey, but despite that oral opinion and knowing, as I did, that no appeal was possible, I did obtain a written advice from the silk in the case. I forwarded that to the prisoner and hoped that was the last of it.

A week or two elapsed and then the letters started again, begging me to file grounds of appeal. I ignored them. One day after I had been in court I returned to the office to find amongst the usual list of telephone calls to which I needed to respond, a message from the Probation Officer at the Scrubs. I returned his call and he asked me to come and see my client and explain why he was unable to appeal. I agreed somewhat reluctantly to see him the next time I was at the prison, which I knew was only a matter of a couple of days hence.

Once in the interview room I repeated the opinion of the QC and tried to explain why learned counsel thought the verdict was not appealable, in as simple a language as I could muster. The client became very angry and told me I was nothing more than a whore because I did not cover my legs and my head. I told him I was leaving. By this time, he was screaming abuse at me and as I stood up to leave he lunged across the table at me and grabbed me by one arm. He didn’t get any further, as the prison officers had heard him shouting and they seized hold of him by the scruff of his neck and dragged him away from me.

It was a distressing experience and I needed a stiff drink that evening.

Life at the Bar – The Arsonist

Arson is a frightening offence, smoke and flames can not only cause enormous damage but the risk to lives is always present. Early in my legal career a fire at one of the public houses in Blackpool was particularly frightening. Fortunately, no one was hurt, but the fire caused extensive damage to the premises and meant the doors were closed for days in the middle of the holiday season. When the police began to investigate it became obvious that the publican’s son had watched the blaze and taken photographs of the fire appliances.

As the enquiry continued the Sergeant in charge found a scrap book which contained photographs taken at the scene of other fires in Blackpool, newspaper cuttings about other cases of arson and a broken footplate from a fire engine. The publican’s son was arrested and interviewed under caution, during which, although at first denying setting the fire, he did eventually admit that he had. He was charged and I was instructed to represent him.

When the fire broke out the defendant’s parents were not in the property, but his grandmother was and because of that he was charged with arson with intent to endanger life. The fire was attended by three fire engines and put the lives of a large number of firemen at risk.

The young man, my recollection was that he was in his twenties, had an interesting background. He had left school at sixteen and he wanted to join the fire brigade, but his application was refused. He was turned down again when he made further applications. He became obsessed with the fire brigade and set the fire at the public house so that he could watch the fire engines turn up and fight the fire.

The case was heard at the Lancaster Crown Court before a High Court Judge. He pleaded guilty and when the sergeant was called to give evidence of the defendant’s previous convictions, he took a very unusual step. When prosecuting counsel indicated he had no more questions for the officer, the detective sergeant turned to the judge and said, ‘My lord, I do want to say that during the course of the investigation I have spent time talking to the defendant’s grandmother; she is not well and I believe if the defendant was sent to prison it would hasten her death.’

The judge listened carefully to what the officer said and the other mitigation put forward by defence counsel. When he passed sentence he explained to the defendant that the sentence for arson with intent to endanger life was a period in prison, but because of the unusual plea made by the policeman on his behalf he would pass a sentence that allowed the defendant to return to his family within a matter of weeks.

London – Kensington High Street

A stroll through Holland Park, with its colourful flower displays took me onto Kensington High Street by the former Commonwealth Institute

The Commonwealth Institute was designed by Robert Matthew, Sir Robert Matthew, Johnson-Marshall and Partners, architects, and engineered by AJ & JD Harris, of Harris & Sutherland. Construction was started at the end of 1960 and completed in 1962. The project was funded by the UK government, with contributions of materials from Commonwealth countries.

Regarded by English Heritage as the second most important modern building in London, after the Royal Festival Hall, the building had a low brickwork plinth clad in blue-grey glazing. Above this swoops the most striking feature of the building, the complex hyperbolic paraboloid roof, originally made with 25 tonnes of copper donated by the Northern Rhodesia Chamber of Mines. The shape of the roof reflected the architects’ desire to create a “tent in the park”. The gardens featured a large water feature, grass lawns, and a flagpole for each member of the Commonwealth. The interior of the building consists of a dramatic open space, covered in a tent-like concrete shell, with tiered exhibition spaces linked by walkways. Despite its iconic status the building fell into disuse and began to deteriorate. As it was a listed building plans to demolish it were always resisted. Now the garden is a building site, but the ‘tent in the Park’ has retained its original shape without the copper. Still I thought it was looking good and hopefully will provide an exciting new home for the Design Museum.

Kensington High Street is not the fashion centre it used to be – most of that has, I suspect, moved to Westfield just over a mile away. Would it be too much to hope that more independent shops will start of open up along this important thoroughfare. Certainly one has, and an unusual one at that. The shop is an old fashioned hardware store called Skillman and sons. The original Skillman and sons was opened by Alfred Daniel Skillman in 1900. What a super name for someone selling tools. The store was famous for selling everything from watering cans to musical instruments. Today at Skillmans, you will find some of the best hand tools from around the world, together with top quality hardware and ironmongery from the U.K, as well as the most functional cleaning products made from all over Europe and the rest of the world. Would it be too much to hope that more independent shops might open along this important thoroughfare. Certainly one has, and an unusual one at that. The shop is an old fashioned hardware store called Skillman and sons. The original Skillman and sons was opened by Alfred Daniel Skillman in 1900. What a super name for someone selling tools. The store was famous for selling everything from watering cans to musical instruments. Today at Skillmans, you will find some of the best hand tools from around the world, together with top quality hardware and ironmongery from the U.K, as well as the most functional cleaning products made from all over Europe and the rest of the world. See http://www.skillmanandsons.co.uk

Life at the Bar – A question of tactics

When I was still employed as a solicitor, West London Magistrates’ Court was in Southcombe Street W14; a redbrick building with an impressive entrance in white stone. On the floor, as you entered was a mosaic of the Metropolitan Police crest, a reminder that this had been called a police court when it first opened. The name may have been changed, but the court was still run by police officers. They organised the list of defendants and had an office where they collected the fines imposed by the magistrates. Solicitors were allowed into the cell area to take instructions from their clients and that also gave access to the small room at the back of a waiting area where the matron dispensed cups of tea for a small sum. It was here that, if you had made friends with the local CID you would be given a brief outline of the evidence against a client. There was no practice of serving statements in cases that were to be heard by the magistrates. Only if the case was being committed to the Crown Court would a lawyer get to see the evidence against the defendant.

One of the warrant officers, a man known as Jock, was a caricature of a Scotsman, quite tall, balding with a fringe of red hair and a ferocious temper. His role was to run the list for the court. When a defendant arrived at the courthouse, whether on bail or brought by the prison van, they were ticked off on the sheets kept by the warrant officer. A defendant’s lawyer would, after seeing his client, tell the officer what application he would be making to the Magistrate. The policeman would then decide the order in which cases would be called, usually depending on the kind of application. Adjournments where there were no applications usually went first, then applications for bail and pleas in mitigation were left to the end. The solicitors appearing in the case before the magistrate were always keen to get their cases on as soon as possible; there was always more work to be done in the office, or another court to attend.

Jock tended to favour local solicitors when deciding on what order to call cases into court, barristers and out of area solicitors were usually put to the back. However, if for some reason you offended him, your case would be put down the list. It was often difficult to know what you had done to upset him. Not being deferential enough was perhaps the most common offence, but there were others. I soon learnt that the best way of getting my cases on first was to make sure I upset him as early as possible. My cases would go to the bottom of the list, but by the time the hearing began, I could guarantee that other lawyers would also have committed some error and their cases too would be transferred to the bottom and as they did so, my clients would get nearer the top. Just a question of tactics.

Life at the Bar – The Man in the White Suit

I am not referring to the journalist, Martin Bell, who stood for Parliament some years ago but to a solicitor who had an office close to West London Magistrates Court. This was before it moved to being in the shadow of the Hammersmith Flyover. I had only just started working for another local solicitor’s practice as the second string advocate, when the outdoor clerk, a Welsh lady who liked a drink or two or may be three, told me I needed to meet Bob.

‘He’s really good looking, and single,’ she said acknowledging my own status. And so he was, six feet tall, a mop of dark hair and a sonorous voice with just a trace of an accent I recognised as being like my own. He was one of the many Lancastrians who had moved to London hoping to make their fortune in the big city.

When the court doors opened in the morning, the outdoor clerk would dash across the road to see if any of our regular clients were in the cells, and to try and get our share of the unrepresented prisoners. She would then come back into the office and prepare a list of the cases we had to cover. There were two courtrooms in the building and I was meant to do the shorter list, usually with the less serious cases and the man who was the main advocate would do the more important ones. It never seemed to work out that way and I found myself covering most of the work in both courts, which brought me into contact with the ‘man in the white suit.’

Actually it wasn’t his usual choice of dress, he normally wore a grey or navy blue pinstripe, but sometimes in the summer and when he wanted to make a dramatic entrance into court, he wore white. I liked Bob, but quickly worked out that he was not the man for me; far too eccentric.

However we worked well together in the courtroom even though we were competitors for business. A long list of clients meant there was too little time to see them all before the stipendiary magistrate came into court. Bob and I learnt to work the list officer so that our cases were not listed consecutively and so allowing a little time to see a client who had not yet appeared.

Cases in the magistrates’ court can be very amusing, and West London had its quota of fun, often provided by the homeless men who lived on and around Shepherds Bush Green. They were usually brought before the court for being drunk and disorderly, and although we wouldn’t be paid both Bob and I often addressed the court on their behalf. One man, it was impossible to tell his age from his appearance, he was so unkempt in a dirty mac, torn green sweater and a once white shirt was before the court for stealing a tin of salmon. He was one of Bob’s clients and this was one of his white suit days. The contrast could not have been more striking.

The defendant pleaded guilty to the theft and Bob stood up to mitigate on his behalf. He was immediately interrupted by the Magistrate, ‘Your client has been in prison too many times. What am I going to do with him? Send him back for a tin of salmon?’

‘That’s exactly what I am asking you to do. The last time he was in custody, he got his teeth seen to. The upper jaw. He’d like to go back to get his lower ones sorted out. That’s why he stole the tin of salmon. He needs a sentence of a least three months for the prison service to sort that out,’ said Bob.

He got his three months. Whether he got his teeth sorted out, I don’t know because that winter he died of exposure, and it was me and Bob together with the list officer who organised a whip round to pay for his funeral.

Life at the Bar – The Stipendiary Magistrate

During my time in Blackpool I had only appeared in front of lay magistrates. Those upstanding members of the local community who the Lord Chancellor’s Department thought were fit and proper persons to dispense justice to their fellow citizens. They often lacked any real understanding of the law and sometimes struggled to assimilate the facts of a case, but I am sure they did their best. Often they had unqualified staff as court clerks who didn’t know the law either. That has all changed now and court clerks have to be qualified lawyers if they are advising the bench of magistrates on legal matters, and the justices of the peace are given much more thorough training.

My move to live in London, driven by the sexist behaviour in my home county and by my love of the theatre, brought me into contact with a different kind of JP, the stipendiary magistrate. They were a fearsome bunch and, at first, I was a little in awe of them. Over ninety per cent of all criminal cases are dealt with in the magistrates’ courts and the stipendiary magistrates, whether a solicitor or a barrister were much quicker at dealing with cases and expected those appearing in front of them to be brief.

St. John Harmsworth sat at the court in Marlborough Street, in the heart of the West End, next to the London Palladium and just across the road from Liberty’s. He was extremely punctual,  walking briskly into court dressed in a pinstripe suit, a military tie of navy blue and dark red stripes and a fresh rose in his button hole. If he was strict in his interpretation of the law, he was also humane.

walking briskly into court dressed in a pinstripe suit, a military tie of navy blue and dark red stripes and a fresh rose in his button hole. If he was strict in his interpretation of the law, he was also humane.

One morning I was sitting in court waiting for my case to be called on, when a fifty year old was brought into the dock. He had been charged with being drunk and disorderly. The arresting officer (they went to court then) stood in the witness box and said he had stopped the defendant as he been staggering on his feet on Oxford Street at about eight o’ clock that very morning.

‘I spoke to him to ask his name, Sir, and noticed his breath smelt of alcohol, his speech was slurred and he was unsteady on his feet, Sir,’ the policeman said. This was a formula all officers used when describing somebody as drunk.

The warrant officer, the man who controls the order the cases are called before the bench, moved forward and said, ‘He was only released from Pentonville this morning, Sir.’

‘What time were you released from custody?’ said St. John Harmsworth, addressing the man in the dock.

‘Six, Sir.’

‘How did you manage to get drunk between six and eight?’

‘Well, your honour.’ (Defendants in the magistrates’ court frequently get the form of address wrong. Only Crown Court Judges are addressed as Your Honour.) ‘It’s my birthday and the lads in the kitchen at Pentonville brewed some hooch and we spent the night drinking.’

St. John Harmsworth looked at the charge sheet in front of him. ‘So it is. Well as it’s your birthday I’ll fine you five pounds or one day,’ he said. There was no need to explain to the defendant that t one day meant he was to stay in custody for the remainder of the court day. It was a common way of dealing with those whose offences were minor and means were limited.

As the prisoner was being led away the learned magistrate said to the warrant officer, ‘Release him as soon as he’s sobered up.’

In these changing times I was a little sad to see the court I had been to so often is now a boutique hotel.

Sheep and Literature

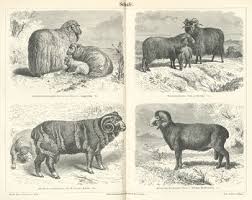

If you have ever wondered on why a book is the size it is, other than something you can hold easily in your hand then you are not alone. When I first qualified as a lawyer, long before the days of the computer and A4 sized sheets of paper, we used a paper size we called ‘brief size’. The secretaries had typewriters, (remember those ) with elongated carriages to take the paper. When is was folded in half it was roughly the same as the current A4. Instead of typing along the short side, briefs to counsel were typed along the other longer side and then they were folded in four and tied with pink tape. When a solicitor was preparing the bill for a case in which they had instructed a barrister, one of the items on the account was the number of folio’s in the brief and that was arrived at by counting a certain number of words, I think it was 72. Of course, the word is used to define a piece of paper folded in two giving four pages in total. But why is a book clearly made up of many folio’s the physical size it is? The answer lies with the size of a medieval sheep.

Paper was first invented in China, but it was the Egyptians that brought it to the west and they used papyrus to make it, which is where the word paper comes from. There wasn’t any papyrus plants in the UK so they used something medieval Britain did have plenty of – sheepskins. Once the skin has been treated and cut into a rectangle, and then folded in half, the ‘pages’ are the size of a modern atlas and that is called a folio. Folded in half again; this is the size of a modern encyclopaedia and is called a quarto. Another fold gives the size of most hardback books and is an octavo. One more fold would give you the size of a mass market paperback. But it does depend on the size of your sheep.

I am grateful to Mark Forsyth for his explanation in his wonderful book The Etymologicon of how and why books are the size they are and where the words to describe them came from.

Life at the Bar – Going Equiped

The offence of going equipped to commit burglary doesn’t seem to feature in the courts these days, but as an articled clerk I was sent to sit behind Mark Carlisle on just such a case. The two defendants, both male, had been apprehended in one of the lanes in the countryside, inland of Blackpool. The evidence against them consisted of observations by the police to whom they were well known and the various objects found inside their car, a grey Vauxhall, I think.

The offence took place on a summer’s evening when an observant police officer had seen the two men, Ken and Norman, driving along a narrow lane that led down towards the River Wyre. He knew it was a dead end, so he radioed for help and an unmarked car arrived. When the Vauxhall emerged from the lane and turned along the main road, the police care followed at a discreet distance. The car then turned down another of the lanes which went towards the River, another dead end. The police stayed on the main road keeping watch. This was repeated a third time, but this time the police followed and as it reached the entrance to a large house sat in extensive grounds, they indicated the Vauxhall was to pull over.

Norman and Ken got out of the car and went to meet the officers. As the two policemen, DC Smith and DC McKie, approached Norman, he pulled his wallet from the back pocket of his trousers and began searching through it.

‘Here’s my driving licence and I’ve got insurance as well,’ Norman said, waving the pieces of paper under the DC Smith’s nose.

‘Thanks,’ said the officer, pushing away Norman’s arm. ‘Let’s have a look in the car shall we.’

All four men strode over towards the car. ‘What you doing round here?’ DC McKie said. He rolled his r’s and looked straight at Ken, who dropped his gaze.

‘Looking for work. Been told some guy wanted a job on his roof,’ Ken said.

‘What’s this guy’s name then?’ McKie said.

‘Don’t know, just told where he lived.’

By this time they had all reached the vehicle and the two officers opened the boot. Inside was a bag of tools, spanners, screw drivers, a couple of hammers, and laid across the base the dark metal of a crowbar glinted in the low summer sun.

‘Doing a roof were we; with a crowbar.’ McKie wasn’t expecting an answer.

Norman spluttered. ‘Yes, guv. We were going to see this guy about some work.’

‘Where does he live, this bloke you were going to see?’ Smith said, as he opened the front passenger door.

On the floor was a piece of paper torn from a reporter’s notepad, the type anyone can buy in WH Smith’s. ‘We had a map…’ Ken pushed past the officer, leant into the vehicle and picked up the sheet of paper. ‘We’d met this guy in the pub. Said he had a few jobs we could do and he drew this map of where his house was. Here, see.’ He thrust the piece of paper into DC Smith’s hand.

The map had been drawn by an inexpert hand, but it clearly showed a lane of the main Cleveleys to Singleton Road. The drawing showed two or three houses along a twisting lane that led down to towards the River.

DC Smith sucked his teeth as he contemplated whether to arrest the two men. He didn’t believe a word they were saying, but with a good defence lawyer they would probably be acquitted. Was it worth the paperwork involved; whatever they were up to they had been stopped in their tracks.

‘Well not sure…’ he said, but was interrupted by DC McKie who was holding a book in his hand.

‘What’s this. A copy of Who’s Who. Now what would you be wanting with this then?’

They were arrested and charged with going equipped with a crow bar, spanners, various tools and a copy of Who’s Who. Despite Mr Carlisle best endeavours both men were convicted.

Life at the Bar – Discretion Statement.

Before the law on Divorce altered in the early 1970’s the petitioner – that’s the person seeking the divorce- had to establish one of a number of matrimonial offences. Cruelty, adultery, or separation for two years were the main causes I remember. And because it was an equitable relief, the clue is in the word petitioner, the husband or wife seeking the divorce had to come to the court ‘with clean hands.’ In practice this caused a lot of problems as very often the petitioner was in another relationship and so the courts had established the procedure known as the discretion statement. In effect, the erring party asked the court to grant their petition for a divorce notwithstanding their own adultery.

Before the law on Divorce altered in the early 1970’s the petitioner – that’s the person seeking the divorce- had to establish one of a number of matrimonial offences. Cruelty, adultery, or separation for two years were the main causes I remember. And because it was an equitable relief, the clue is in the word petitioner, the husband or wife seeking the divorce had to come to the court ‘with clean hands.’ In practice this caused a lot of problems as very often the petitioner was in another relationship and so the courts had established the procedure known as the discretion statement. In effect, the erring party asked the court to grant their petition for a divorce notwithstanding their own adultery.

Soon after I qualified as a solicitor I had just such a case. The wife, Helen Broad was a glamorous blonde, and she had left her husband and was living with another man. She and I discussed at length how to deal with her discretion statement and agreed on a wording that essentially said she had entered into another relationship and had committed adultery on numerous occasions over the preceding two years. The statement was signed by her and placed in a sealed envelope, as was the practice.

On the day of the hearing of Helen Broad’s petition, we met the barrister, David Fox, I had instructed to appear on her behalf, in the waiting area of the County Court. He towered over both me and the client, as I introduced her to him.

Helen was wearing a pale camel coat, her long hair was loose and she had bright red lipstick. She was the best-looking woman in the room and David took her hand and held onto it for a little longer than necessary, before directing us to a quiet a corner where he could discuss the case and try to put Helen at ease. David manoeuvred his not inconsiderable bulk down onto a chair and pulled it up close to where we were sitting on a bench.

‘Is there a discretion statement?’ he said.

I searched through my file and handed him the brown envelope containing the carefully crafted disclosure. He opened it, his heavy fingers tearing the paper apart and rather more carefully opened the piece of paper inside. He fished his glasses out of his top pocket of his dark pin-striped suit and began to read. The petitioner watched him, her mouth in a wide smile but the eyes suggested she was a little wary.

David looked over the top of his glasses, ‘Don’t you know how many times you have committed adultery?’

Helen Broad looked him straight in the face and said, ‘I don’t count, do you?’